As a Japanese person, it is interesting for me to find English words that were adopted from Japanese, like edamame, kaiju, karaoke, koi, origami, satsuma, umami, and etc. These words are called loanwords. Loanword (also loan word or loan-word) is a word at least partly assimilated from one language into another language through the process of borrowing.

I’d like to talk about loanwords that were adopted into Japanese from Portuguese this time. In addition to a list of loanwords, I added the information about 当て字(ateji) for Japanese learners and differences between ベランダ(verandas) and バルコニー(balconies) in Japanese for people who are curious about living in Japan in the future.

(目次=Table of contents)

What are 借用語(shakuyougo) and 外来語(gairaigo)?

Before discussing the main part of loanwords from Portuguese to Japanese, please let me explain that there are two different translations of loanword in Japanese. One is 借用語(shakuyougo) and the other one is 外来語 (gairaigo). How to separate shakuyougo and gairaigo depends on academic researchers, but I separated them according to Japanese common sense in this article. If you want to check a list of loanwords first, please click this link.

借用語(shakuyougo) from three languages, kango, Ainu and Ryukyuan languages

借用(shakuyou) literally means to borrow and use in Japanese. 語(go) means word, term or language. 借用語(shakuyougo) indicates words that were adopted into Japanese from other languages including 漢語(kango), アイヌ語(Ainu language), 琉球語(Ryukyuan languages), and etc. The brief explanations of each language are as follows.

漢語(kango)

Kango is originated from Early Middle Chinese. Since kango is written in 漢字(kanji) and became a part of Japanese language during the 5th to 7th century, most Japanese people are not aware that they are using kango as shakuyougo in everyday life. There are a lot of kango used as nouns in Japanese. For example, the verb “walk” [歩く (aruku)] is a native Japanese word and the noun “walking” [歩行 (hokou)] is kango. You can also use 歩くこと (arukukoto) for “walking”, which is a native Japanese word, but 歩行 is shorter and used more frequently.

アイヌ語 (Ainu go = Ainu language)

If you have watched the anime called ゴールデンカムイ(GOLDEN KAMUY), you already know who the Ainu people are and that their language is very different from Japanese, so you can skip reading this part. The Ainu are an indigenous ethnic group who reside in northern Japan (mainly in Hokkaido prefecture) and southeastern Russia. Strictly speaking, Ainu language in Hokkaido and southeastern Russia are not exactly the same, so loanwords from the Ainu language are from the Hokkaido Ainu language.

- Examples of loanwords from Ainu language:

- 昆布(konbu = kelp)

- 鮭(sake = salmon)

- ラッコ(rakko = sea otter)

- トナカイ(tonakai = reindeer)

- シシャモ (shishamo = a type of smelt that is native to Hokkaido) and etc.

- It is said that around 80% of place names in Hokkaido are from the Ainu language and they have been written in kanji since the Meiji period (1868-1912).

GOLDEN KAMUY manga volume 1-24 collection is available on AMAZON. (Amazon Link) You can learn the Hokkaido Ainu culture by reading this manga!

琉球語 or 琉球諸語 (Ryukyu go or Ryukyu shogo = Ryukyuan languages)

There was a kingdom called the Ryukyu kingdom (1429-1879) in the current Okinawa prefecture and Amami islands in Kagoshima prefecture. Ryukyuan languages refers to 6 languages (including about 35 different dialects) spoken in different areas and islands in the region, and they may be considered as dialects within Japanese language presently. Like the Ainu language, they also sound very different from standard Japanese, and I, who was born and grew up in Tokyo, cannot understand them at all. There is a dialect called 沖縄大和口(uchinā yamato guchi) where Ryukyuan language and standard Japanese are mixed, and I can understand some words because of TV shows.

- Examples of loanwords from Ryukyuan languages:

- ゴーヤー(gōyā = bitter melon)

- チャンプルー(chanpurū = the general term of Okinawan stir fried dishes)

- ミミガー(mimigā = cooked pig’s ear)

- シークヮーサー (shīkuwāsā = a small citrus fruit that is native to Okinawa and Taiwan)

- and place names in Okinawa prefecture (they have been written in kanji since around 1609)

外来語 (gairaigo) Mainly from Western Languages

In a broad sense, 外来語(gairaigo) is the same as 借用語(shakuyougo). 外来(gairai) literally means “from foreign” or “from outside”, and 語(go) means word, term, or language. It can be translated as foreign words in English. When Japanese people refer to gairaigo, it generally means words that were adopted mainly from Western languages not kango, Ainu or Ryukyuan languages. Therefore, it is more commmon to regard gairaigo as a type of shakuyougo. カタカナ(katakana) is usually used to write gairaigo.

You need to keep in mind that some gairaigo don’t have exact the same meaning as the original words. The English translations on the list in this article is for the translation of gairaigo and not for the original language.

A List of Gairaigo from Portuguese (Introduced to Japan from 1543 to 1639)

Portugal was the first European country that Japan had cultural exchange and trading with in its history. It started in 1543 (in the Muromachi period) when a Chinese ship with Chinese and Portuguese crews washed ashore on Tanegashima island located in Kagoshima prefecture, Kyushu region of Japan. All Japanese students learn about this event in Japanese history class because it was the moment where 鉄砲(teppou = matchlock firearms) was introduced to Japan (and eventually drastically changed the style of samurai battles).

After that, Japan started importing items such as firearms, gunpowder, silk (from China*¹) from Portugal and exporting silver, gold, Japanese swords and etc. to them.

*¹Portuguese ships called at ports in China before coming to Japan at that time.

| Portuguese | Gairaigo | English translation of gairaigo |

|---|---|---|

| balanço | ブランコ (buranko) | swing |

| bolo | ボーロ*² (bōro) | a type of Japanese snack |

| botão | ボタン (botan) | button |

| camboja | 南瓜 (kabocha) | pumpkin, squash |

| capa | 合羽*³ (kappa) | raincoat |

| carta | カルタ、歌留多、加留多 (karuta) | karuta, Japanese playing cards |

| pão de Castella | カステラ (kasutera) | castella, a type of Japanese sponge cake |

| confeito | 金平糖 (konpeitō) | konpeitō, a type of Japanese sugar candy |

| copo | コップ*⁴ (koppu) | cup without a handle |

| inglês | イギリス (igirisu) | the UK |

| gibão | 襦袢 (juban) | undershirt worn with a kimono |

| jorro | ジョウロ、如雨露 (jouro) | watering can |

| ombro | おんぶ (onbu) | piggyback ride |

| pão | パン (pan) | bread |

| sabão | シャボン、シャボン玉*⁵ (shabon, shabon dama) | soap bubble |

| tabaco | タバコ、煙草 (tabako) | cigarette |

| tempero, têmporas | 天ぷら、天婦羅、天麩羅 (tenpura) | tempura |

| varanda | ベランダ*⁶ (beranda) | veranda |

*² ボーロ (bōro)

The original word, bolo means cake in Portuguese, but Japanese ボーロ means a type of baked confectionery that is bite size and mainly flour (sometimes potato starch or buckwheat flour), sugar, milk, and egg. It is not too sweet, and it has a very light texture.

*³ 合羽 (kappa)

The sound, kappa, is exactly the same as 河童(kappa) that is a name of a yōkai (= a class of supernatural entities and spirits in Japanese folklore) living in a river or swamp. Some Japanese people still use the word 合羽(kappa) or 雨合羽(amagappa) when they refer to a raincoat, but mainly レインコート(rein cōto) is used recently.

*⁴ コップ (koppu) and カップ (kappu)

There is a theory that コップ(koppu) is originated from the Dutch word, kop. If you are studying Japanese, you may have heard the word, カップ(kappu). Both コップ and カップ mean “a cup” in English, but there is a difference between these two words in Japanese. コップ usually means a cup without a handle and カップ means a cup with a handle.

コップ and カップ are called doublets in linguistics. Doublets are words in a given language that share the same etymological root, and they are often the result of loanwords being borrowed from other languages. コップ came from Portuguese or Dutch, and カップ came from English.

*⁵ シャボン (shabon)

Japanese people don’t use the word シャボン(shabon) in daily life, but use the word シャボン玉(shabon dama) for soap bubbles that children play with or performers use at shows.

*⁶ ベランダ(beranda) and バルコニー(barukonī)

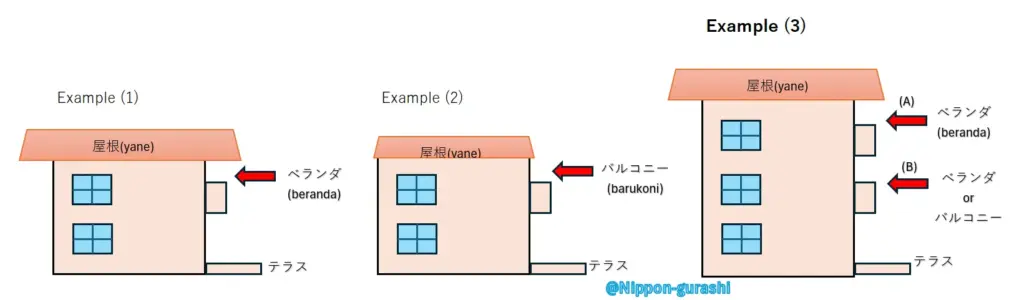

Unfortunately, there are many Japanese people who get ベランダ(beranda = veranda) mixed with バルコニー(barukonī = balcony), and I was also one of them. It seems like the definition of these two words in English is different from Japanese. In Japanese, ベランダ is a roofed porch (at least on the second floor or above) that is attached to the outside of a building. On the other hand, バルコニー is a platform projecting from the wall of a building, and there is no roof.

The biggest difference between Japanese ベランダ and バルコニー is basically whether there is a roof or not. Why did Japanese people get confused with this simple difference? I think it is because there is no clear definition of the words, ベランダ and バルコニー by the Japanese Building Standards Act that elucidates matters concerning the site, construction, equipment, and use of buildings. Therefore, architectural design companies, housing companies, or construction companies in Japan can use those terms based on their own definitions and they could be different depending on the company.

The Japanese word 屋根(yane = usually translated into “a roof” in English) has two meanings, and first one is a roof and the second one is a thing that covers the top of something. Some people think (B) in the example (3) is ベランダ because the ベランダ of the above floor covers the top of the space. Others think it is バルコニー because the ベランダ of the above floor is not a roof.

What is 当て字 (ateji) ?

You may wonder why there are kanji words in the list of gairaigo from Portuguese to Japanese, even though I have mentioned it is common to use katakana to write gairaigo. Those kanji are special and they are called 当て字(ateji). 当て(ate) has many meanings but it means to assign in this case, and 字(ji) literally means character or letter. If I simply say what ateji is, it is a substitute character (with kanji).

Ateji principally refers to kanji used to phonetically represent native or borrowed words with less regard to the underlying meaning of the characters. For instance, kanji from the list, 金平糖, 襦袢, 如雨露, and 天麩羅(天婦羅) are ateji that have phonetic equivalents with the original words. On the other hand, ateji also refers to kanji used semantically without regard to the readings. It is said that 合羽, 南瓜 and 煙草 are ateji that ignore the pronunciations of kanji and consider only meanings.

Ateji for gairaigo was used often until the end of the Edo period (1603-1868). After the Meiji period (1868-1912), Japanese people started using more katakana when they wrote new gairaigo, and in the Taisho period (1912 – 1926) and the Showa period (1926-1989) they completely stopped using ateji for new gairaigo coming to Japan.

The use of Ateji in Manga

Although ateji has been rare to see in daily life, ateji is commonly used in manga (especially shōnen manga). Ateji are used for character names, names of techniques, skills, abilities and etc. ONE PIECE, for example, is one manga where the author uses a lot of ateji. There is a kicking attack called 悪魔風脚 that a main character, Sanji uses in battle. If you normally read the kanji 悪魔風脚, it should be like あくまふうあし(akumafū ashi). 悪魔風(akumafū) literally means devilish, and 脚(ashi or kyaku) means legs. However, the correct reading of this attack is 悪魔風脚(deiaburo janbu = Diablo Jumbe) in the manga.

Diablo Jumbe came from French (jambe du/à la diable), but most Japanese readers cannot understand what it means if it is written only in katakana. In this case, the kanji that were used as ateji help readers to comprehend the meaning of the attack’s name. You may wonder why the author did not use the Japanese reading あくまふうあし (akumafū ashi) from the beginning if Japanese readers cannot understand ディアブロジャンブ (deiaburo janbu). Well, it is the author’s preference, and personally I agree with the author’s idea because the French phrase sounds cooler than the Japanese one. I think that the French phrases in Sanji’s attacks emphasizes that he is a chef (although we don’t know if he is a French style chef or not in the manga or anime) and not only a mere fighter of the Straw Hat Pirates.

I don’t think many viewers of anime in Japan pay attention to the meaning of attacks, techniques, or skills very much since dynamic action (or battle) scenes are the main point of watching an anime that is based on shōnen manga. Unlike reading manga, watching an attack in an anime is easier to understand, so it is normal that anime characters just say the katakana name of their attacks.

If you are studying Japanese and curious about the difference between gairaigo and 和製英語(wasei-eigo), please check this article as well!

References

Embassy of Japan in Portugal (in Japanese) https://www.pt.emb-japan.go.jp/itprtop_ja/index.html

National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics (in Japanese) https://kotobaken.jp/qa/yokuaru/qa-95/

KOZA WEB OKINAWA CITY (in Japanese) https://www.kozaweb.jp/featureCategories/show/16